I met this man, dressed to the nines in honor of the momentous day of celebration and homage, wearing a beige trench coat and an ascot cap. He was standing on the steps of the historic Tabernacle Baptist Church, on Broad Street. I approached him, and said hello. He noticed my cameras, and my photojournalist vest, which didn’t deter him from responding to my greeting. We struck up a conversation. He told me that he had come up from Florida the day before, taking the night bus. He arrived in Selma that morning, well before daybreak, only to find that all of the motels were full. He spent the remainder of the night in the bus station.

My awareness was guided to this preacher who stopped at the end of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, after making his pilgrimage walk across, and back again. It wasn’t just the awareness of him standing there. It was the acute awareness of his posture, and the way he held his hands clasped together, combined with the emotion of his gaze that was directed into town less than fifty yards away from where he stood. I had a strong sense that he had been here, fifty years ago, as a much younger man. But to approach him, to engage him in conversation, would have been an invasion, so I made the photograph and moved on.

I noticed this young African-American boy, dressed in a suit, and tie, emerging from the bridge. This awareness afforded me the time to watch, and study the scene as it unfolded, so that I could position myself in the best possible way to capture the story that wanted to be told. He walked with, what I presumed to be, family members: mother, father, and older brother perhaps. As I dropped to one knee and raised the camera to my face, they were well aware of my presence, as well as my intention to make a photograph of them. As the grew closer, and were very near to passing by, the young boy grabbed his necktie with one hand and I released the shutter. For me it is a quintessential image of what the day represented. The gray clouds thatThe had begun to break in the sky above the bridge. This young black boy, walking ahead of his family members as if leading the way into his future, and out of the tragedies, violence, and hatred of the past. He symbolized hope for us all.

Blues Highway Visitor Center

The Visitor Center along Mississippi 61, better known as the Blues Highway, not only has a very nostalgic feel, but it is also a plethora of informaion about the Blues heritage.

Barbee Cemetery

As the story goes, legendary bluesman, Robert Johnson sold his soul to the devil at the crossroads - which allegedly are in the town of Clarksdale, Mississippi. I have it on solid authority, however, that the place where Robert Johnson spent his time ( as well as possibly “selling his soul to the devil”) was in the Barbee Cemetery on the outskirts of Clarksdale, along Highway 61, also known as the “Blues Highway”.

The Hollywood

The Hollywood took me by surprise. I was looking for a place to have lunch on my way out of the Delta. A local suggested The Hollywood, saying that they had the best burgers around, and then gave me directions.

As I pulled off of Old Highway 61, turning right onto Old Commerce Road, I turned left into the nearly empty parking lot, went inside, and chose a table near the back.

In the corner, near the entrance door, was an old piano. On the walls were memorabilia photographs, including one of a black woman playing a piano that look quite like the one near he entrance.

There were also several posters of the singer/songwriter, Marc Cohen, hanging on the brick walls. I was baffled by th

s, so when the waitress came to take my order, I inquired. She said that this is the place that Marc Cohen wrote about in his hit song: “Walking In Memphis”. This is where he came to play piano with Muriel - who was the woman in the photograph I mentioned.

“Muriel plays piano, every Friday at The Hollywood.

And they brought me down to see her, and asked me if I would

Do a little number and I sang with all my might.

She said, tell me are you a Christian child, and I said

Maam I am tonight!”

Interior of The Hollywood

Painted Facade/Indianola, Mississippi

Deke Harp

Henry Gip Gipson

Nickson's Juke Joint / Tunica, Mississippi

I had heard of "quilting circles" but had never witnessed one until now. It is the quintessential community activity. Every week, women in Arnaudville, Louisiana, gather at the Arnaudville Art Center to sit around a large table and create a quilt.

In truth, the quilt-making is simply a pretext for these women to come together, spend time in fellowship, and talk.

Crawfishing is a vibrant tradition deeply ingrained in the fabric of Louisiana's heritage that has been passed down from generation to generation.

But crawfishing isn't merely about the catch—it's a way of life. It's about community, family, and a connection to the land. As the season wanes, the flooded fields, once teeming with crustaceans, transform into fertile grounds for another Cajun staple: rice. It's a seamless transition, a cycle of sustenance and tradition that embodies the resilience and resourcefulness of Cajun culture.

Beyond its practical significance, crawfishing encapsulates the spirit of Louisiana—a blend of resilience, ingenuity, and a deep reverence for the land. It's a tradition that transcends time, weaving itself into the very identity of Cajun communities and serving as a testament to their enduring heritage. In every trap pulled from the waters, there lies a story—a story of resilience, of connection, and of the unwavering spirit that defines Cajun culture.

Checking the Crawfish Traps at Sunrise

Crawfishing begins early in the morning, just as the sun rises above the horizon. For the traps set close to the shoreline the fisherman simply walk out. The water level throughout the ponds is a uniform depth of about three feet.

Espresso Yourself Cafe

Cafe’s, in general, have always been a gathering place for both locals, as well as outsiders passing through.

Espresso Yourself Coffee Shop that had located along Main Street in the heart of Grafton, became an essential part of this community. It was the hub of the community in so many ways. It was also the place that I based myself out of while working in Grafton.

One day, while in the cafe, I watched these three teenage girls sitting around the table giggling, and sharing stories of their lives. Instead of each sitting autonomously with their phones, they were engaging face to face.

Tomb of the Unknown Soldier/Grafton, West Virginia

In the older of the two National Cemeteries in Grafton, West Virginia, is a “tomb of the unknown soldier” - a large marker representing those whose bodies were never recovered, or identified.

It is in the cemetery that the annual Memorial Day Parade culminates. Speeches are delivered, and various ceremonies are enacted.

In each of these the devotion and respect by all in attendance is profound. This is also a tradition of respect and honor that continues to be passed on from parents to children - as it has since the very first celebration.

Bell Ringer

As part of the Memorial Day celebration at the National Cemetery in Grafton, a veteran rings a large bell to honor the dead, and to signal the salute of the American Flag.

This honor, to be chosen to ring the bell, is not taken lightly. The reverence to its significance is profoundly apparent.

A Salute of Deep Reverence

During the ceremonies at the National Cemetery on Memorial Day, I observed the man tasked with ringing the bell to honor the fallen.

He stood at attention throughout the proceedings, his solemn demeanor evident as he fulfilled his duty. After tolling the bell, he pivoted to face the American Flag and delivered a salute. It was not a perfunctory gesture; rather, it reflected his profound reverence for the flag's symbolism and, equally, his respect for all Americans who made the ultimate sacrifice in every war.

Along a desolate two-lane highway that leads to the rim of the Grand Canyon, small merchant stands are set up in a large dirt parking lot carved out of the barren landscape.

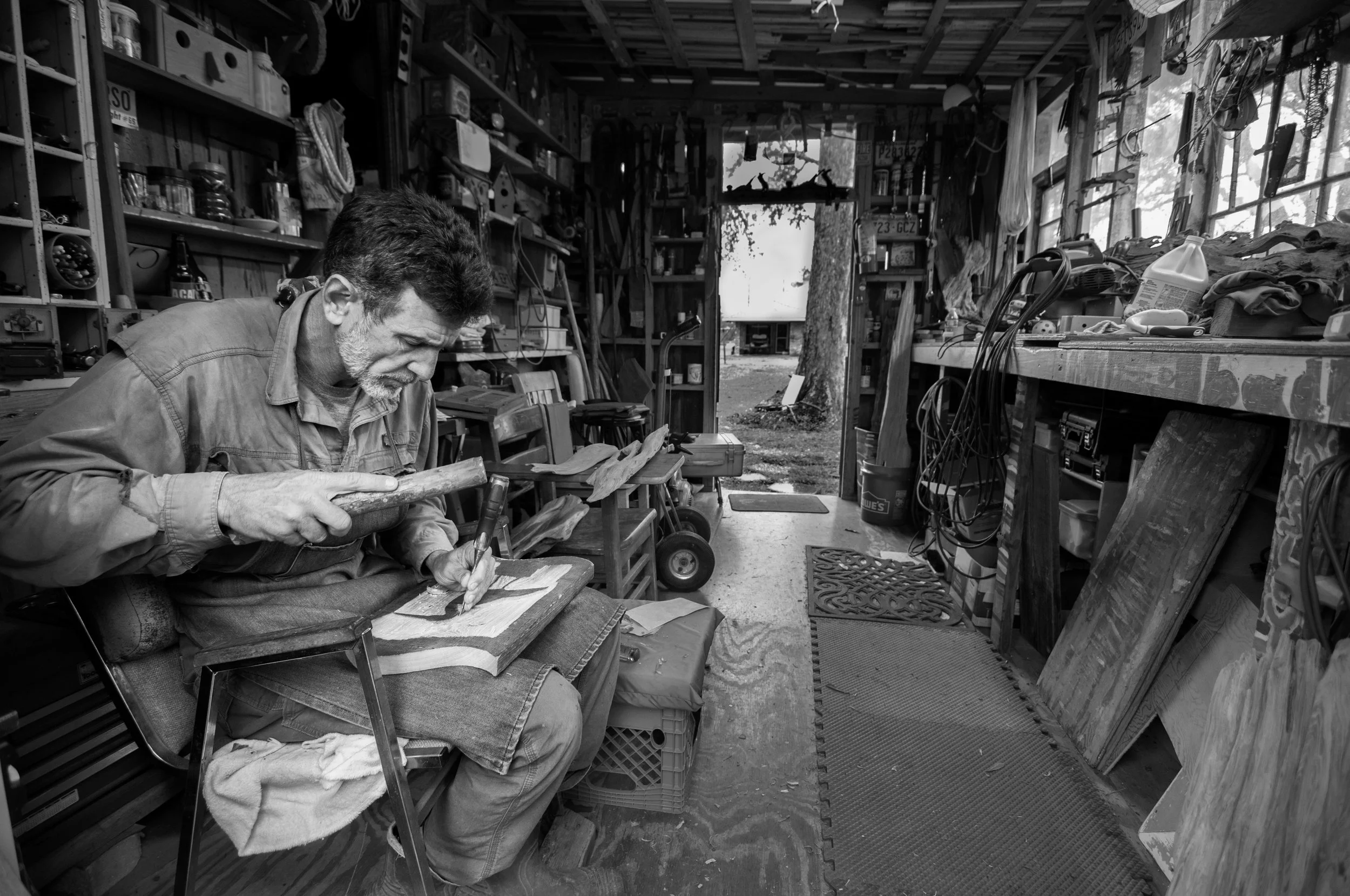

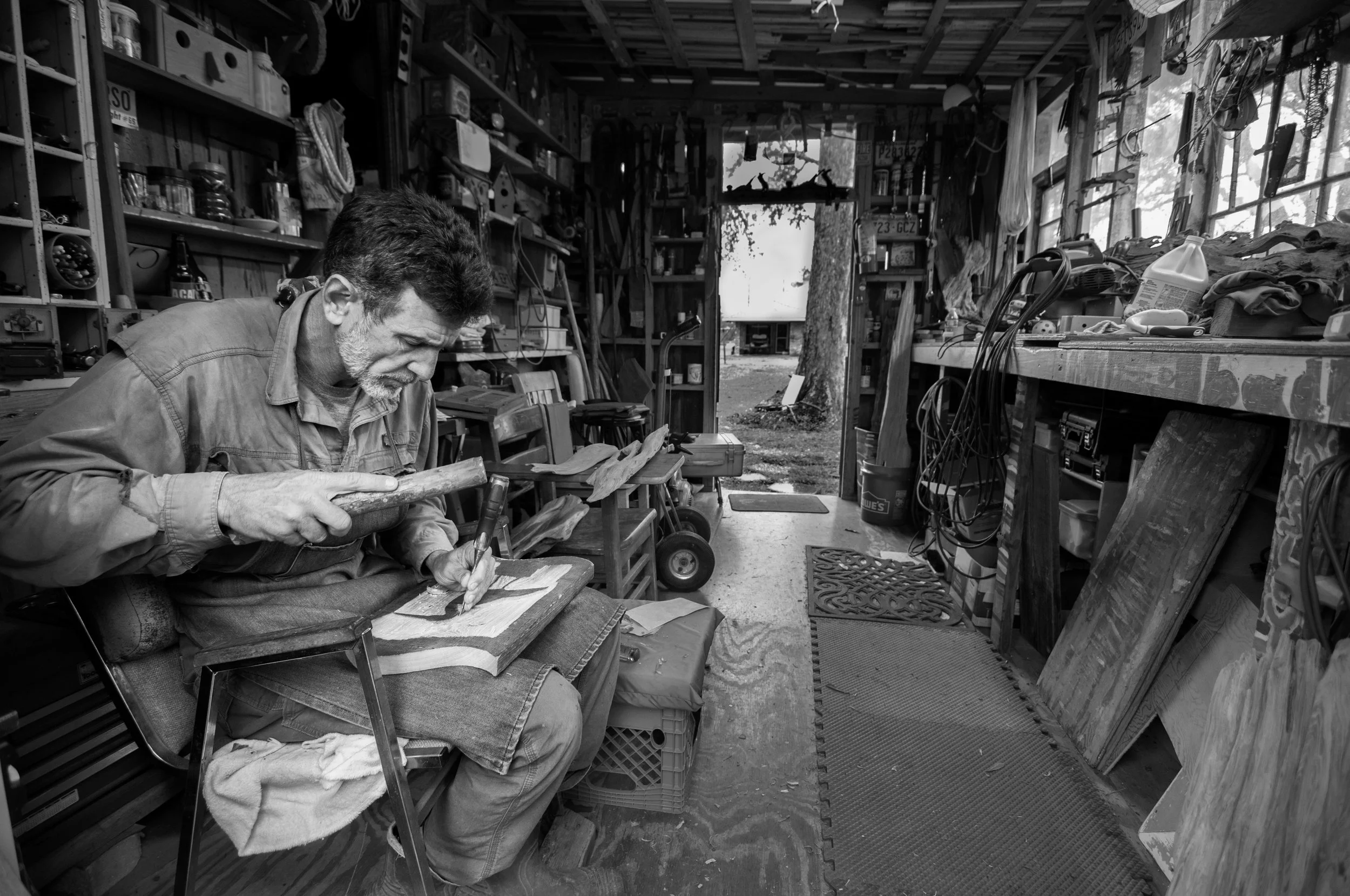

This Dine’ (Navajo) artisan carves line drawings on pieces of flat local stone - much in the same method of those who carved the petroglyphs thousands of years ago.

Helen Grayeyes, a traditional Dine’s (Navajo) woman who 94 years old at the time of this photograph. Every morning she ‘wakes, gets dressed, feeds the dogs, runs one mile down her road and back again, then herds her sheep’. Helen speaks no English, and lives alone in her house that is seven miles after the paved road ends. The rock formations that surround her house are abundant with Uranium, which has been mined by the U.S. government for decades, causing major health problems for residents of this area.

Alice, who is Dine’ (Navajo) makes traditional Fry Bread in Helen’s kitchen. Fry Bread is common among many of the Indigenous tribes of the United States, and is a staple of their diet.

Jackson, who was thirteen years old at the time of this photograph, is a Lakota Fancy Dancer. His specific title is Grass Dancer. Fancy Dancers are part of the Lakota reviving their traditions.

Jackson is a Lakota Fancy Dancer, and his persona is a Grass Dancer. When he dances the dance, as well as the attire represent the tall prairie grasses of their homeland moving in the wind.

Johnny Tire Repair

Throughout the Dine’s Reservation one sees signs for “tire repair”. Seemingly every couple of miles one of these signs will be at the end of a long dirt driveway that leads to someone’s home. This is one of the few ways that Dine’ can earn a living.

Navajo Families Need Jobs

The lack of jobs on the Dine Reservation is staggering. There is no industry to speak of, nor is there much of a business district in each of the small towns.

Navajo College

Jobs and job training are lacking throughout the Dine Reservation. A Technical College was established in the town of Chinle (pronounced: Chin Lee), which has helped significantly.

Selling Hay

Hay can not be grown in sufficient amounts in New Mexico and Arizona. Because of this the hay must be brought from Colorado. Throughout the Rez land in New Mexico there are many hay vendors set up along the roadsides. The hay is priced by the quality.

A sheep is laid on a table, or on the ground and held in place while the thick winter-coat of wool is sheared. Most Dine’ (Navajo) still use manual shears, instead of electric shears, which makes the process extremely labor-intensive.

These two men carry a sheared sheep by the legs to a pen that is separate from the sheep still waiting to be sheared. The sheep is carried so that it doesn’t run off into the open vast landscape.

As the wool is sheared from the sheep it is piled on a large plastic tarp. Once much as accumulated, it will be gathered by hand and packed into long tubular sacks for transportation to the collective warehouse.

As the wool is sheared from the sheep it is piled on a large plastic tarp. Once much as accumulated, it will be gathered by hand and packed into long tubular sacks for transportation to the collective warehouse.

The buildings of the Pueblo are made solely from adobe, which is earth mixed with straw and water. The walls are commonly several feet thick.

Periodically maintenance needs to be performed by applying new mud to the walls.

The current residents ofTaos Pueblo are the descendants of the original settlers, which began occupying the settlement between 1000 and 1450 A.D.

There are currently about 150 people living within the Pueblo full time, and still remain more than 1900 Taos People living on the surrounding Taos Pueblo lands.

The buildings of the Pueblo are made solely from adobe, which is earth mixed with straw and water. The walls are commonly several feet thick.

Periodically maintenance needs to be performed by applying new mud to the walls.

The current residents ofTaos Pueblo are the descendants of the original settlers, which began occupying the settlement between 1000 and 1450 A.D.

There are currently about 150 people living within the Pueblo full time, and still remain more than 1900 Taos People living on the surrounding Taos Pueblo lands.

Periodically the adobe needs to be repaired. This is accomplished by applying new adobe mud to the walls. In this image one can see the smoothness of the repaired section near the wooden steps.

Coal miners, at the Leer Mine in Taylor County, West Virginia, wait at the elevator to take them down into the mine shafts which spider off in several directions, and spread out for miles.

Coal miners, at the Leer Mine in Taylor County, West Virginia, wait as the previous shift emerges from the elevator that connects above ground with the mine.

.

Deep underground, and several miles from the elevator shaft that brought us down, miners work in an area that is extremely loud, with narrow walkways and a ceiling that is barely above one’s head. There is a constant danger working in these conditions, and not just from the most obvious such as a collapse. There are thick pneumatic cables, as well as electrical cables everywhere, and heavy machinery in constant motion, with giant cutting blades that strip the coal from the seam walls.

The Chili Pot

BJ Fokakis, the fourth generation of the family-owned diner: The Coney Island Cafe, in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, holds the infamous copper-lined pot hat has ben used by each generation to make the famous chile for the Cafe’s chili dogs.

Coney Island Cafe

Early morning prep for the breakfast rush. Sabrina, who has been the head cook at the Cafe for years, arrives about an hour before the Cafe opens, to begin prepping the bacon and sausage.

Ray

Ray has been a regular at the Coney Island Cafe for years. Every morning Ray, along with a few other regulars, arrives at the cafe - generally sitting at the same tables and booths, to discuss the current events of the days.

At on point I overhear Ray mentioning that he raises chickens. Several minutes later, when here was a break in the conversations, I asked him how many chickens he had. “24,000”, he responded in a matter-of-fact way.

I was shocked! I had thought maybe a few dozen.

As we continued the discussion he filled me in on he commercial ins and outs of raising chickens - including how to govern the specific size of he fully grown chicken.

As I was driving to Gillette, Wyoming for the annual Buck n’ Ball, and of course the annual Chicken Roping Competition, I passed by Devil’s Tower National Monument.

I found an irony with this sign in the middle of nowhere. The open desolation of a snow-covered landscape broken by a sign offering the weary traveler a shot of caffeine. Sadly, after driving for miles in all directions, tehre was no coffee house to be found.

The handmade wooden sign nailed to an old tree along State Highway 22 near Samburg, Tennessee.

Along Interstate 71 just south of Columbus Ohio.

This, for me, was a scene that may have been very reminiscent of the day of the crucifixion when Jesus was nailed to the cross. On the opposite side of the boardwalk was a pizza shop. Atop the pizza shop backed by the sky, was a statue of a short, chubby, Italian looking man wearing a white Baker’s jacket and hat. His arms raised and stretched outward as if he were a representation of God welcoming His son home. Just beneath this statue standing on the boardwalk was a young chubby boy wearing a bright red shirt, who had just emerged from the front doors of the pizza shop. A boxed pizza in his left hand and an ice cream cone in his right. He just stood there facing the man with the cross coming as if anticipating the coming crucifixion. From the left of the frame emerged a couple walking past the man with a cross, seemingly not paying attention at all. Coming from the other direction were a single horizontal line of teenage girls who also seemed oblivious to the man with a cross. Could all of these elements - not just the man with a cross, be some sort of modern representation of the scene that unfolded more than 2,000 years ago?

It can be read in scripture that Jesus was paraded through the streets carrying his heavy cross, and at times stumbling, and if memory serves me, even falling. Scripture tells us that the people who lined the sidewalks jeered at Jesus, spat upon him, and more. But I don’t remember reading what the people did after Jesus passed by.

Did they join the procession to Calvary, to did they return to the daily lives? On Calvary itself did hordes of people gather or was it just another crucifixion? We know from history that crucifixions during this time of the Roman occupation were quite common. Did people bring refreshments to the crucifixion? I am reminded of the horrific stories of our recent history in the United States, during the time of racial segregation where blacks were routinely hung from the branches of trees and people gathered with picnic baskets and cameras. Could this have been a similar situation during the crucifixion of Jesus.